Annual measurements were made in Askja in August

Landris in Askja continues, but there are no signs that the magma is moving closer to the surface

2.9.2024

- The land continues to measure up to Askja.

- It is considered probable that magma accumulates at a depth of about 3 km

- No evidence of magma moving closer to the surface

An annual field trip was made to Askja last August, the trip is a joint project of the Icelandic Meteorological Office, the Institute of Geosciences of the University of Iceland and the University of Gothenburg. The field trip included geodetic measurements (level and GNSS measurements), pH and temperature measurements in Vítis crater, as well as multiple gas measurements (CO 2 , H 2 S and SO 2 ) in the steam hot spring area in Vítisgíg.

The results support what is seen from continuous GPS measurements and from recent InSAR images, that landrising continues in Askja, but at a slower rate since September 2023. However, there are no signs that magma is moving deeper into the Earth's crust.

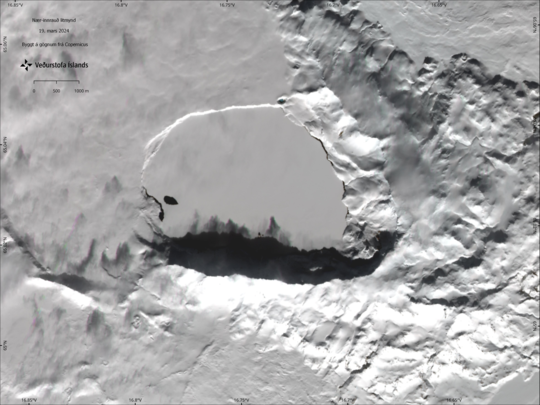

About 12 cm of land has been measured at the GNSS station OLAC (west of Öskjuvatn) in the last 12 months. InSAR satellite data and tilt measurements confirm ongoing landrising. The results of modeling calculations indicate that the location and depth of magma accumulation in the area is similar to what has been previously estimated. It is believed that the flow is about 3 kilometers deep. There are no signs of magma movements moving closer to the surface. Model calculations indicate that 4.4 million cubic meters have been added in the last 12 months. Therefore, it is estimated that the total change in volume since the beginning of the land in July 2021 is now about 44 million cubic meters.

Measurements made in Víti show no significant changes (pH, water temperature and chemistry).

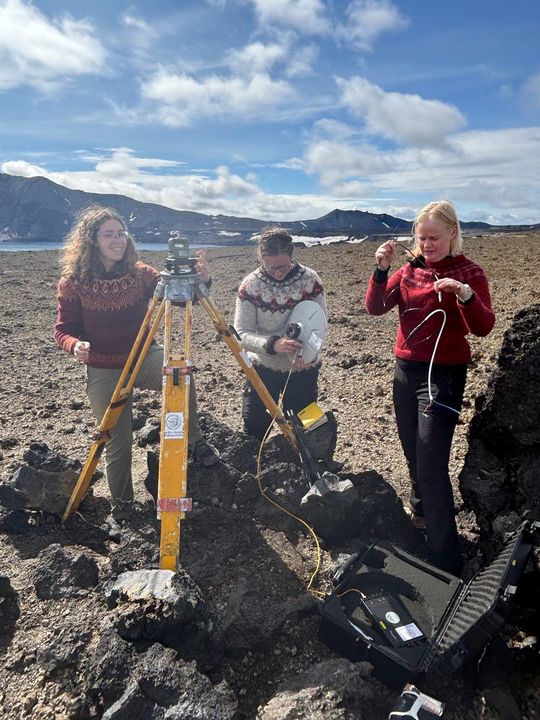

Doctoral students Catherine O'Hara and Sonja Greiner (from the University of Iceland) together with Dr. Ástu Rut Hjartardóttir (Meteorological Office of Iceland) performs GNSS measurements at station MASK on the northern edge of Öskjuvatn (photo: Michelle M. Parks/Meteorological Office of Iceland).

Doctoral students Catherine O'Hara and Sonja Greiner (from the University of Iceland) together with Dr. Ástu Rut Hjartardóttir (Meteorological Office of Iceland) performs GNSS measurements at station MASK on the northern edge of Öskjuvatn (photo: Michelle M. Parks/Meteorological Office of Iceland).

The development in Askja will continue to be closely monitored. After landrising began and expansion was noticed at Öskja in the summer of 2021, monitoring has been increased significantly.

The first deformation measurements in Öskja were slope measurements that started in 1966, and between 1970 and 1972 landris were measured. But after a break in measurements for a few years due to the Kraflu fire, slope measurements began again and then the land began to subside, and this trend continued until 2021 when the land surface began to be measured again. Land has been measured before without an eruption. At this stage, it is therefore difficult to assess how things will develop in Askja.

The omens were clear when there was an eruption in Askja in 1961

The last eruption in Öskja was in 1961 when Vikrahraun was formed in an alkaline lava eruption, but such eruptions are the most common eruptions of the volcano. Similar eruptions occurred at the beginning of the 20th century. The lead-up to the eruption in 1961 was clear, but 20 days before it began, increased seismic activity was measured and a significant increase in geothermal activity. During the period 6.-12. October 1961, six earthquakes of magnitude 3 were measured, one of which was magnitude 4, and powerful geothermal springs formed in areas where there had been no activity before.

About four acid explosive eruptions are known in modern times (the last 11 thousand years), the youngest occurred on January 3, 1875. The eve of that eruption began at least in February 1874 with increased geothermal activity, and strong and frequent earthquakes (recorded in the North) started weeks before the eruption. In 1875, alkaline lava flows also erupted on Askja's fissure zone, Sveinagjárgosin, where, among other things, Nýjahraun was formed. In light of history, where a long time passes between acidic explosive eruptions in Askja, it is not considered likely that a sequence of events similar to the one that took place at the end of the 19th century will begin in the coming seasons. It is most likely that the consequences of continued activity will be volcanic eruptions comparable to those that have occurred in the 20th century, i.e. relatively small lava eruptions with minor pyroclastic fall. If there is an eruption at the bottom of Öskjuvatn, however, an explosive eruption can be expected while the magma is isolating itself from the water.

www.express.co.uk

www.express.co.uk